At this important crossroads in the Sustainable Eel Group’s journey, where our work is set to extend to all eighteen species of river eel, we write to reaffirm our dedication to a vision of responsible management that is comprehensive and indivisible; and grounded in the Brundtland understanding that ecological integrity, social continuity, and economic viability must be pursued together. To treat these dimensions as separable is, we believe, to weaken the very possibility of recovery, for the eel is not simply a species in crisis but a thread connecting ecosystems, communities, and markets. The challenge before us is to show that conservation and continuity can coexist, that fishers can act as custodians of the stock, and that the sector can be reshaped to secure its own future within the limits of ecological renewal.

In the European Union, the Eel Regulation continues to provide the most coherent framework for achieving these ends. Its dual benchmarks – the long-term aim of restoring 40 percent of pristine biomass and the short-term objective of achieving 40 percent survival of the current stock – are both measurable and quantifiable and therefore provide essential reference points for our analysis. They reflect the biology of the species, which matures slowly and recovers only over the course of generations, and they remain the most credible standards for action. As with many continent-level policies, the implementation has been uneven, but the principle is clear: success depends on collecting more catch data, not less; on reinforcing the Regulation with deadlines that focus political will; and on shielding it from dilution or drift. SEG continues to argue that 2030 must stand as the horizon by which a minimum protection standard is secured, and that progress will only be possible if these commitments are pursued.

Evolution of eel policy in the European context

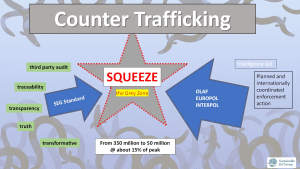

The future of European eel policy lies less in designing new measures than in ensuring that those already agreed are carried out with consistency and accountability. EU Member States must align their national management plans with predetermined reference points, report transparently on their progress, and submit to independent review that strengthens credibility. They should think more seriously about cross-border operations with the potential to close regulatory loopholes, disrupting criminal networks and the trade they support. But, most importantly, the protection of the eel must also be approached comprehensively, encompassing not only fisheries but the full spectrum of human impacts, from barriers that impede migration to the degradation of habitats and direct mortalities from hydropower operations. The Regulation was designed to address these cumulative pressures in an integrated way, and its success depends on that integrative vision being realised in practice. Only by focusing on improvements to implementation and cooperation will European stakeholders deliver on the promises they have made.

Across the channel, the challenge takes a distinct form, shaped by the absence of large commercial players and the continued presence of traditional, small-scale fisheries. In this context, SEG has placed emphasis on defending conservation fishing as a practice that preserves ecosystems and cultural heritage, recognising that recovery cannot be secured by conservation science alone and must be embedded within communities that have fished for centuries. The Severn and Parrett fisheries illustrate how carefully managed harvesting can contribute to broader ecological goals when paired with transparent governance and an agreed conservation purpose. However, they also reveal the vulnerabilities that arise when destinations for catches cannot be independently assured. The low-level priority restocking initiatives are allocated by the UK authorities, combined with the pressure from some quarters for exports to markets that cannot guarantee ethical or traceable use, has left fishers without secure avenues for contributing to recovery. In response, new models are beginning to emerge: projects in Somerset and Gloucestershire demonstrate how conservation fishing can be reorientated toward direct contributions to restocking, linking cultural continuity to measurable ecological benefit. Northern Ireland presents its own complexities, with the algal blooms in Lough Neagh emblematic of the need to ensure the commitments made by the fishery are matched in other industries, including agriculture, energy, water supply and treatment. Here, as elsewhere, the decisive factor will be whether governments, local authorities, utilities companies, and NGOs are prepared to invest in structures that allow traditional fisheries to become instruments of conservation and development.

The inclusion of European eel in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) has enhanced oversight and control across its range, and yet illegal exports continue, frequently facilitated by mislabelling practices that obscure the true identity of shipments. Because the glass eels and meat of the various freshwater eel species are virtually indistinguishable by sight, customs authorities are often forced to rely on DNA barcoding, a method that, while scientifically robust, is widely regarded as expensive, impractical, and logistically difficult to implement at scale. The limitations of this technology are particularly acute in developing countries, where resource constraints place reliable molecular diagnostics out of reach and, in turn, create uneven enforcement capacity that can concentrate criminal activity in regions least equipped to manage it. In the current regulatory context, a double-edged problem persists, where, even in regions where trade is legally sanctioned, consumer demand is readily displaced onto other freshwater eel species, generating parallel pressures across the genus that current species-specific protections are ill-suited to address.

Evolution of eel policy beyond Europe

Beyond Europe, the need for coherence is sharpened by the global character of the species and the scale of the trade that surrounds it. Aquaculture supplies the majority of eels consumed worldwide, but every farmed eel still originates from juveniles taken from the wild, embedding vulnerability into the system from the bottom up. This structural dependence, coupled with growing international demand and the indistinguishability of freshwater eel species as meat and at early life stages, has created opportunities for trafficking and mislabelling on a scale that undermines conservation and legitimate commerce. The absence of transparency has eroded consumer confidence, weakened lawful industry, and diverted stock that should contribute to population recovery into unregulated markets. SEG has argued consistently that traceability is not a bureaucratic burden but the condition of responsible management; and that, without a transparent supply chain, the ecological, social, and economic pillars collapse in on each other. Ensuring full traceability across borders with modern monitoring technologies and enforceable oversight is the only way to guarantee that global trade aligns with the long-term survival of the species.

For this reason, SEG supports the proposal to extend CITES Appendix II protections to all river eels, thereby eliminating the loopholes that partial listings leave open. A comprehensive listing is essential in light of the fact that enforcement cannot depend upon the ability to distinguish between glass eels and eel meat, and only universal coverage can prevent substitution and trafficking. Such measures strengthen conservation by ensuring that juveniles are channelled toward legitimate and traceable use, but they also protect commerce by establishing uniform standards across markets and jurisdictions. Freshwater eels are panmictic species whose spawning grounds lie in remote ocean gyres and whose migrations connect rivers from Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas. Their recovery requires a governance framework commensurate with its range. In this sense, global action is not ancillary to recovery but its precondition, and SEG will continue to work with governments, civil society, and industry to press for the standards necessary to secure ecological and commercial futures.

The Sustainable Eel Group’s dedication to this cause is unaltered by the difficulty of the task or the length of the recovery horizon. We will continue to advocate for the rigorous implementation of the European framework, the recognition of conservation fishing as an instrument of ecological and cultural continuity in the United Kingdom and Ireland, and the establishment of international mechanisms that ensure transparency, eliminate illegality, and provide a coherent global standard. Recovery will be slow, dictated by the biology of the species, yet the slow pace only underscores the urgency of immediate action. To secure the future of the eel requires consistency, inclusivity, and endurance; to fail would be to accept the erosion of both biodiversity and heritage. SEG remains steadfast in its conviction that restoration is possible, provided that the environmental, the social, and the economic are held together.

Recent developments and their significance

Recent developments in France highlight the risks that remain when transparency and enforcement do not keep pace with market demand. In March, coordinated raids in Vendée and Charente-Maritime led to the arrest of seven people, including five professional fishermen, accused of exporting glass eels illegally to Spain. The operation, which involved more than eighty agents from the French Office for Biodiversity and the gendarmerie, uncovered clandestine holding tanks, large sums of cash, multiple bank accounts, and a collection of vehicles that included a Porsche 718. Prosecutors estimated that the ecological damage caused by this trafficking network over an eighteen-month period amounted to nearly half a million euros, reflecting the scale of stock diverted from regulated fisheries and conservation programmes into illicit markets. The case is now before the court in La Roche-sur-Yon, with the defendants facing potential sentences of up to seven years in prison and fines of €750,000.

Proceedings in neighbouring departments have revealed similar practices, showing that this network was not unique but rather one example of a wider pattern. Cases reported on the Sèvre Niortaise and in coastal estuaries detail how traffickers exploit opportunities created by fragmented enforcement, fishing under cover of night, manipulating weighing procedures to disguise the true size of catches, and using Spain as a point of transit for shipments destined for Asian aquaculture markets. The economic incentives driving this activity are considerable. In France, a kilo of elvers can fetch around €400, but in Asia, the same quantity may be worth as much as €6,000. It is this disparity that fuels these networks, drawing in licensed professionals as well as organised criminal actors, and creating pressures that national authorities struggle to contain even when prosecutions are pursued with vigour.

The significance of these cases lies not only in the prosecutions themselves but in what they reveal about the structural vulnerabilities of the current system. Professional fishermen, ostensibly operating within regulated frameworks, can still be drawn into illicit activity when oversight is incomplete and when cross-border coordination is weak, even within the single market. Reports from France Bleu, Ouest-France, France 3, and Le Marin make clear that these are not isolated incidents but recurring examples of a systemic problem, in which enforcement gaps at the international level create opportunities for exploitation. While the penalties being pursued in French courts may serve as a deterrent, deterrence alone will not be sufficient if the conditions that enable the trade are unaddressed.

This is why SEG continues to call for comprehensive traceability in the supply chain and for international cooperation that matches the global nature of the market. National enforcement actions, however robust, can only ever treat the symptoms of a problem that is transnational in scope. The trafficking networks dismantled in France illustrate the consequences of a system in which demand far exceeds the capacity of regulators to respond, and in which partial protections invite substitution and evasion. They reinforce the case for the inclusion of all freshwater eel species in CITES Appendix II and for the creation of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms that reduce the scope for illicit trade. Without such measures, the ecological losses will continue, legitimate fisheries will be undermined, and public confidence in conservation will erode. With them, the recovery of the eel stands a real chance of success.

Further reading

For recent reporting on glass eel trafficking and the associated legal proceedings in western France, see:

-

France Bleu: “Trafic de civelles: des pêcheurs professionnels de Vendée et de Charente-Maritime jugés à La Roche-sur-Yon”

-

France 3 Régions: “Trafic de civelles: des peines de prison requises contre dix pêcheurs”

-

Ouest-France: “Pêche de nuit, fausse pesée, transport en Espagne: un important trafic de civelles jugé en Vendée”

-

France Bleu: “On a besoin d’épurer ce type de réseau: des pêcheurs vendéens et charentais jugés pour trafic de civelles”

-

Marine & Oceans: “Trafic de civelles: des peines de prison ferme requises”

-

TV Vendée: “Pêche: plusieurs pêcheurs poursuivis pour un trafic illégal de 466 kilos de civelles”

-

Le Marin (Ouest-France): “Cinq pêcheurs professionnels jugés pour trafic de civelles sur la Sèvre Niortaise”